As the Browns’ sensational speedster Travis Benjamin writhed in pain in Kansas City on October 27, 2013, his attempt to twist free on a punt return instead tearing up his knee, more than a few fans were dejected but not entirely surprised.

Benjamin, after all, is listed at just 175 pounds. His true weight is 170, he would acknowledge at an off-season Browns Backers club banquet. With a body type more greyhound than mastiff, he was hardly expected to withstand the full onslaught of pro tacklers, fall after fall.

|

| Browns trainers tend to Benjamin. Plain Dealer photo. |

After surgery and rehab for the torn ACL that ended his 2013 season, Benjamin made one other change that may prove crucial to his prognosis as a player: a different jersey number. He wanted to switch from 80 to 10. Subsequent signee Earl Bennett was given 10, so Benjamin swapped with another receiver coming off ACL surgery, Charles Johnson, sporting number 11.

This isn’t to make light of an orthopedic trauma. Trotting out numerology risks trivializing a very real injury. No, this is more serious than dallying with digits.

The truth is, over the past 43 years, if you suited up for Cleveland wearing the number 80, it became your career’s kiss of death.

This isn’t about an unfixable jinx or unprovable curse. It’s about fully airing the facts of a persistent and perplexing pattern.

No matter your pedigree, your position, salary, size, or race, it was bound to take place. More than likely, you’d get hurt. Regardless of the reasons, without exception you wouldn’t reach pronounced peak potential. Not while wearing number 80 for the Browns.

For starters, think Brian Robiskie, Kellen Winslow II, Andre Rison and Willis Adams. More than a dozen others have donned the doomed 80 with nary a counterexample. Since 1972, only busts, breakdowns, or bit players.

From Turkey to treachery

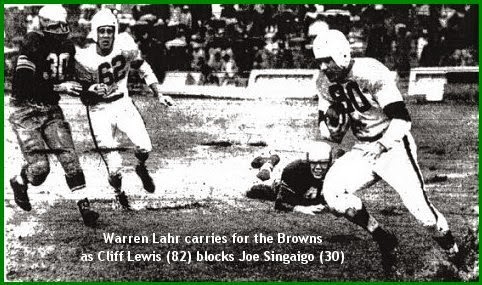

On September 3, 1972, 84,816 fans filed into Ohio Stadium in Columbus for a preseason exhibition with the Cincinnati Bengals, the team founded and coached by the Browns’ legendary exiled namesake, Paul Brown. The first pro game held at the Horseshoe was a back-and-forth battle the Bengals won, 27-21. The Browns also lost an emerging pillar of their defense, third-year end “Turkey” Joe Jones, to a season-ending knee injury in the third quarter.

|

| “Turkey” Joe Jones’ 1972 Topps football card |

Jones missed the Browns’ last playoff team of the decade. He returned in 1973 but was then traded to Philadelphia for washed-up wide receiver Ben Hawkins. Jones’ signature moment — the pile-driving sack of Terry Bradshaw — came during his second stint in Cleveland, when he wore 64 rather than 80. He had a decent career, but it never matched the promise that made him the 36th overall pick in 1970, 11 slots ahead of teammate Jerry Sherk.

The next Brown to wear 80 was Willie Miller, a receiver/returner even smaller than Benjamin. He’d survived two tours in Vietnam, earning a Purple Heart and Silver Star, but the 28-year-old rookie would last just 20 games with the Cleveland squad. Upon recovering from injury, he resurfaced with the Rams and caught 50 passes for 767 yards in 1978, remaining in Los Angeles though age 35.

A similarly slight skill player named Lawrence Williams returned kicks wearing 80 at the tail end of 1977, his second and last year in the league.

The number fell next to the Browns’ top draftee in 1979, Houston wideout Willis Adams. The Browns had traded down from the 13th overall pick to 20, gaining a second rounder: offensive tackle Sam Claphan, who hurt his back and was released a year later. San Diego used the Browns’ pick on Missouri’s Kellen Winslow, who became a Hall of Fame tight end wearing, of course, number 80. As it turned out, Claphan recovered to play 87 NFL games, ironically, all with Winslow on the Chargers’ electric offense.

In contrast, Adams disappointed. It took until the fifth of his seven seasons for him to find the end zone, which he did just twice. His speed kept him on the roster, but he never emerged as a quality starter, even on some pretty thin receiving corps.

|

| Willis Adams gains 15 yards, a career-long rush, on a fake punt, Dec. 7, 1980. Unfortunately, it was fourth-and-17. Plain Dealer photo. |

The next eight players to sport the brown and orange 80 jersey were all receivers or tight ends. Terry Greer, Chris Kelley, Chris Dressel, Vernon Joines, Lynn James,Danny Peebles, Shawn Collins and Tom McLemore averaged fewer than eight games and two receptions as Browns. Only Kelley ever scored, and it was only one point.

Then, in the fateful year of 1995, Browns owner Art Modell made Andre Rison the highest-paid wide receiver in history, luring the free agent with a five-year, $17.5 million deal including $5 million to sign. Intended as a bold move to push a playoff team over the top, the Rison contract headlined an off-season of roster resentment, upheaval and restructuring that hastened the franchise’s plunge into financial peril.

The four-time Pro Bowler started slowly, gaining just 82 yards on nine catches through four games. By mid-season, a team tabbed for Super Bowl contention took a disastrous turn into the rocks. News broke that Modell was moving the 50-year-old Cleveland Browns to Baltimore, and things got ugly. Only a heartfelt home finale kept them from losing their last eight games. Amid the skid and fan backlash, Rison was quoted as “ready to get the hell out of here… Baltimore, here we come.”

But after posting seven-year career lows in receptions, yards, and touchdowns, the original Browns’ last number 80 was released.

New era, more despair

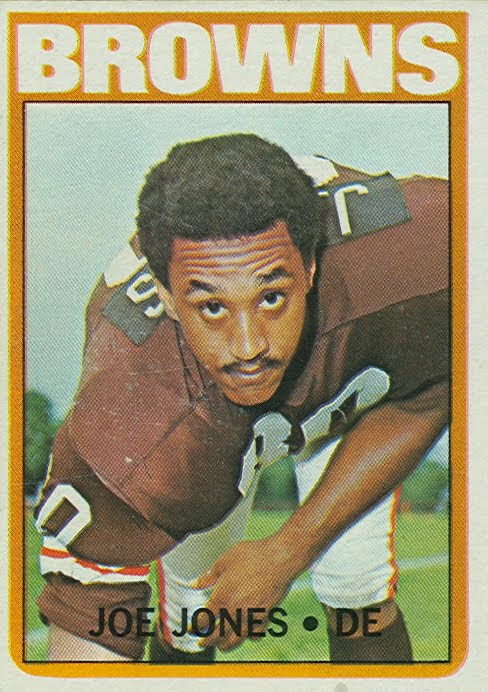

Upon the Browns’ rebirth in 1999, the symbolic futility continued with Ronnie Powell. An undrafted native of Hope, Arkansas, Powell — unlike the town’s more famous product — would not get a second term. In Week 14 at Cincinnati, Powell gained 45 yards on his sole NFL reception, but then sprained his neck during a fumbled kickoff return, ending his rookie year. He was waived the next preseason.

|

| Powell makes one of the Browns’ few advances in their first game back in the league in 1999. (Tom Pidgeon/Allsport) |

Tight end Aaron Shea was a relative bright spot for the 2000 Browns. The fourth-rounder from Michigan took over number 80 and proved tough to tackle. But after a 30-catch, 302-yard rookie year, Shea’s next three seasons all ended the same way: on injured reserve. In 2004, he sold the jersey number to rookie Kellen Winslow II and switched to 83, formerly worn by his ex-Michigan and Browns teammate, Mark Campbell.

Like Turkey Joe in the ’70s, Shea’s career caught second wind wearing another number. He broke a three-year drought with a career-high four touchdowns in 2004. He played six seasons and worked six more for the Browns in sales and player engagement.

Some of Shea’s starts stemmed from Winslow’s well-documented woes. The son of the aforementioned Hall of Fame 1979 trade target was as highly touted as any tight end prospect ever. Butch Davis, who recruited Winslow to the University of Miami before he left to take the Browns’ reins, put all his chips on the table in 2004. He gave Detroit his high second-round pick to inch up one slot, drafting the brash 20-year-old playmaker sixth overall.

Winslow began his troubled Browns career holding out 12 days into training camp before inking a six-year deal that included $16.5 million up front. In a Week 2 loss in Dallas, as he and his teammates surged to recover an onside kick, his right fibula broke. It required two surgeries and ended his rookie year.

His next mishap was decidedly less valiant. On May Day, 2005, he was thrown over the handlebars of his new motorcycle in a Westlake parking lot, sustaining a torn right ACL and other injuries. After hitting a curb at 35 mph, he was lucky to miss only one more season and to not have the Browns claim breach of contract to claw back his bonus.

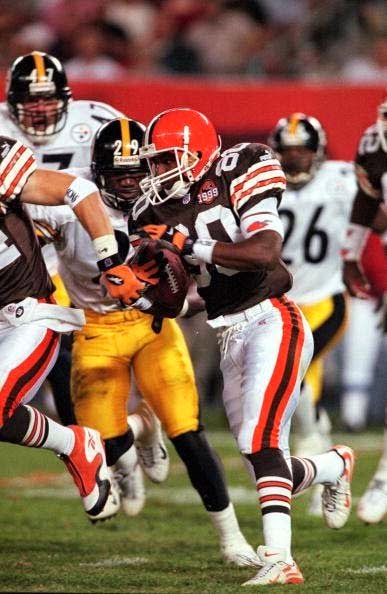

Winslow overcame a post-surgical staph infection to return for two fine seasons, with a combined 171 receptions for 1,981 yards. Despite his Pro Bowl play in 2007, the Browns narrowly missed the playoffs.

The difference may have come down to one judgment call. On the last play of a December game in Arizona, Winslow snagged a 37-yard Derek Anderson pass in the left corner of the end zone. It would’ve set up a winning extra point try, but he was pushed out of bounds, and the officials didn’t rule that both feet would have been in had the defender not forced him out. (The NFL soon changed its rules to eliminate the need for such judgment calls, so now a force-out can never be ruled a completion.)

|

| This play not being ruled a force out likely cost the Browns a 2007 playoff berth, prompting a rule change months later. AP photo. |

Things went south for both the Browns and Winslow in 2008. Injuries and in-house turmoil led to a 4-12 record and a thorough organizational housecleaning. Winslow missed time with another staph infection and provoked the ire of general manager Phil Savage with some pointed public comments about the Browns’ role in it. Savage suspended him, but it was overruled after it emerged that a team employee had urged Winslow to keep news of the staph under wraps.

Winslow’s tenure in Cleveland certainly perpetuated the pattern plaguing those who wore his number. Of the 80 Browns games between his drafting and eventual trade to Tampa Bay, he appeared in just 44. He showed outstanding hands and competitive fire, but injuries robbed him of the speed to separate from defenders and the power to break tackles or block effectively. He also committed too many penalties. In 2013, he was suspended from the Jets, his fifth team, for violating the league’s policy against performance enhancing drugs.

The number 80 next landed upon another ex-player’s son. Brian Robiskie grew up in the Cleveland area while his father, Terry, was a Browns assistant coach. The Buckeye was widely considered among the most “NFL-ready” receiving prospects in 2009, when the Browns drafted him 36th overall.

Since 1999, the Browns have used second-round picks on eight wide receivers. Robiskie was the least productive of them all. He had just 39 catches and three touchdowns in 31 games when the team waived him midseason in 2011. He last played for Atlanta, where his father is the receivers coach.

So when Travis Benjamin became the 25th Brown to don these dangerous digits, it became a question of not whether but when something bad would befall him. Though unaware of the background behind his jersey number, his instinct to change it appears sound.

He broke Eric Metcalf‘s franchise’s record with 179 punt return yards in a win over Buffalo and had become an increasingly important big-play weapon by the time of his injury three weeks later. Now wearing number 11, Benjamin appears to have fully returned to form in 2015, not only as a returner, but as the team’s best deep threat on offense.

Meanwhile, the man signed to fill the role of the Browns’ number one receiver, Dwayne Bowe, has been hampered with a hamstring injury and has yet to impress the coaching staff. Fans in on this numerical trend may be disappointed but unsurprised at the lack of production from this latest wearer of number 80.

But all this history does not so far explain the logic behind this unmistakable pattern. Is it just a statistical oddity borne from vulnerable positions in an inherently risky sport? Possibly, maybe even probably. It certainly is uncanny, though, especially when the dials of Browns history are turned back to 1972 and before.

Worn with distinction

Prior to Turkey Joe’s knee injury, he hadn’t missed a game and was developing apace to succeed Ron Snidow, an All Pro in 1969 at left defensive end. In fact, before 1972, several Browns had worn number 80 to great effect.

Al Akins had a 50-yard touchdown run in the Browns’ inaugural season of 1946. Bob Cowan scored eight times in two years and contributed to the undefeated 1948 team.

But this was mere prelude. The next five Browns to wear the 80 jersey — spanning the AAFC era to the NFL/AFL merger — all excelled during long, distinguished careers.

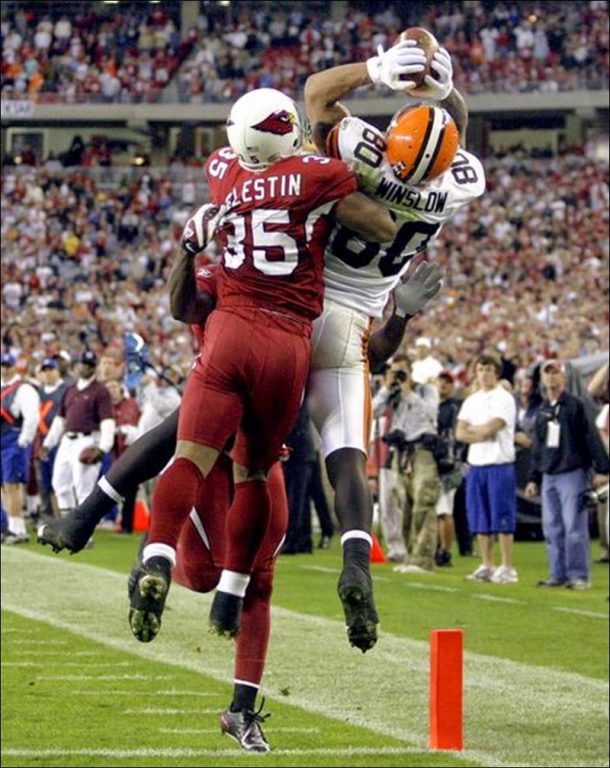

Warren Lahr wore it for his first three seasons (1949-1951) before the numbering system was first revamped. He played defensive halfback (now called cornerback) through 1959 and still ranks second behind Thom Darden in career interceptions for the Browns – first, if AAFC and playoff games are included.

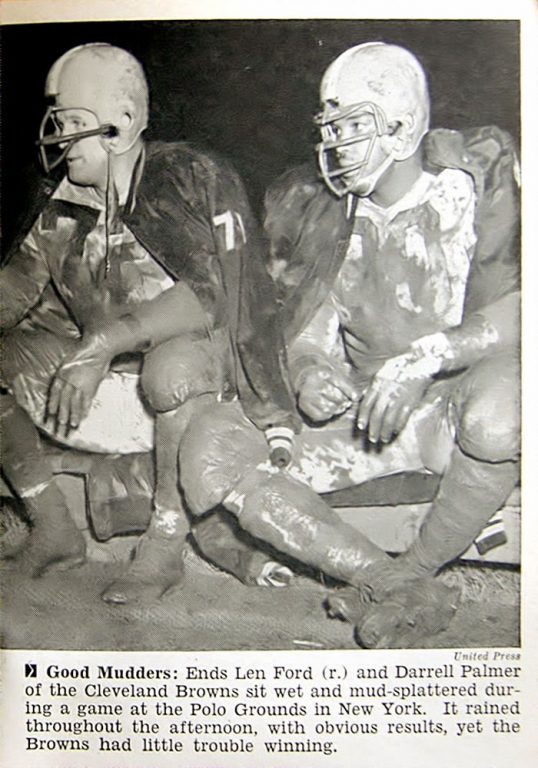

The great defensive end Len Ford switched from 53 to 80 beginning in 1952 and played most of his remarkable 11-year career in the jersey number at issue.

Offensive tackle Dick Schafrath wore 80 as a rookie in 1959 before donning 77 for the duration of his legendary career. So too did his former Ohio State teammate Jim Marshall in 1960, before he was traded to Minnesota and set iron-man records as a Purple People Eater.

Bill Glass came to Browns Town in a 1962 trade with Detroit. The tall Texan earned Pro Bowl honors his first three seasons in Cleveland and again in 1967 for his pass-rushing prowess. No Brown to this day has worn number 80 for more games than the durable Glass. Any credible version of an all-time, all-Browns team would include both Glass and Ford, two otherwise very different men, as the defensive ends.

|

| Bill Glass lowers the boom on the Giants’ Y.A. Tittle. Ron Kuntz UPI photo. |

Glass had never missed a game until broken ribs sidelined him late in 1968. He then retired to pursue his successful and still-active prison ministry, now known as Bill Glass Champions for Life.

On Sunday, January 19, 1969, Lahr died of a heart attack on his living room couch in the Cleveland suburb of Aurora. On Thursday, his doctor had given him a clean bill of health. He played tennis on Friday. He fell ill on Saturday and took it for the flu. His post-retirement career had included TV color commentary for the Browns. He was 45 and left behind a wife and five daughters.

Lahr was the first alumnus of the Browns’ number 80 to pass away. The next would be Ford.

An enigmatic legend

Leonard Guy Ford Jr. was a supreme talent who emerged during a trying but transformative time for blacks in American society. The Washington D.C. native was all-city and a team captain in three sports. He enrolled at historically-black Morgan State (as did Leroy Kelly two decades later) and starred as a two-way end. He served in the navy as World War II ended, then transferred to the larger stage of Michigan, although he was denied the chance to play basketball there on account of his race.

The 6-foot-4 Ford was tenacious as a tackler and a scoring threat on offense. An Associated Press profile from 1947 quoted him as liking to “mix it up” on the field, while “[i]n practice his never ending stream of quips and jibs is often a welcome balm when nerves and tempers become frayed.” He shined at the 1948 Rose Bowl, as the Wolverines trounced USC, 49-0, to cap a perfect season.

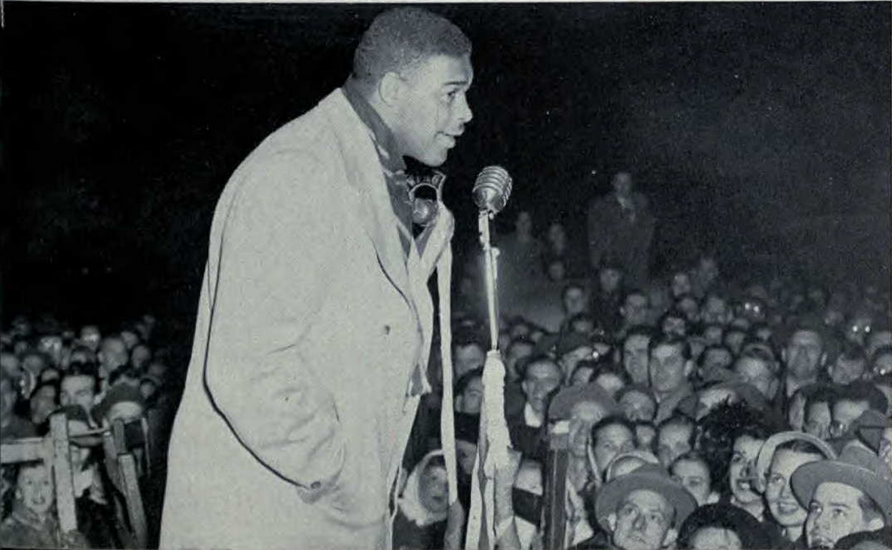

|

| Ford addresses Michigan fans upon returning from the Wolverines’ 1948 Rose Bowl triumph. (UM yearbook photo) |

In Ann Arbor he dated Geraldine Bledsoe, a promising student and daughter of a prominent Detroit attorney. Ford earned a bachelor’s degree in education from UM.

Despite two years of All-American recognition, Ford was undrafted by the NFL. Most teams still didn’t employ African American players. The Los Angeles Dons picked him 15th overall in the 1948 All-America Football Conference draft. “He has everything — great size, speed, strength, great hands,” said Dons’ coach Jimmy Phelan.

Ford played on both sides of the ball with the Dons, gaining 1,175 yards on 67 catches his first two seasons (17.5 YPC). He led AAFC rookies with seven receiving touchdowns.

After the AAFC folded in 1949, the NFL held a draft of players from disbanded clubs. Successful with black players from the beginning, Cleveland’s Paul Brown brought Ford back to the Great Lakes region with his second pick. The Browns were well-stocked with ends, but the coach figured Ford’s aggressiveness would help his defense.

In Brown’s memoir, he said Ford “supposedly had an attitude problem” but it was “really nothing more than hating to be on a losing team.” Ford’s days on offense were over. He’d get his hands on the ball only by interception or, more frequently, recovering fumbles, which he did a then-record 20 times over the next nine seasons.

Ford’s adjustment to the NFL was harsh. Early in the Browns’ first game of 1950 at Philadelphia, he got called for clipping, nullifying a long touchdown. Brown looked at the film and declared it “not a clip, but instead one of the greatest blocks ever thrown on a punt return — Len Ford had wiped out three Eagles’ players in one move!”

The Browns won anyway, but Ford would soon face a much tougher recovery. An elbow from Chicago Cardinals’ fullback Pat Harder fractured multiple facial bones and cost him several teeth. Harder, pass blocking, swung at the relentless Ford’s cheek, which in this era was unprotected by a face mask. Ford needed extensive plastic surgery and his jaw wired shut, and he missed the rest of the regular season rehabbing. By the way, there was an ejection for that play: the officials tossed Ford.

Ten weeks later, sporting a custom cage and down in weight from a liquid diet, he returned to stuff Ram runners and harass passer Bob Waterfield mightily in the epic 1950 title game, which ended, by the way, not with Lou Groza‘s famous field goal, but with #80 Warren Lahr’s second interception of the game.

|

| From the 1950 NFL championship game in Cleveland, Warren Lahr (80) is at left, while at right is Len Ford (53), protecting his injured face with an oversized facemask. (Plain Dealer file photo) |

That off-season, after her law school graduation, Geraldine Bledsoe and Ford married in Detroit, where their family soon included two daughters. Brown recalled Ford as a “gentle soul” off the field, and one of his favorites on it, “a fierce player and something to behold when he uncoiled and went after a passer.”

Sadly, little film of that era exists to behold, and no quarterback sack statistics were kept, official or not. Glass is credited with the team’s single-season sack record (14.5), with Clay Matthews owning the career record of 76.5.

Ford’s exceptional determination as an athlete, it should be said, was undermined by being “his own worst enemy in the way that he took care of himself,” as Brown put it.

Some teammates were more direct. In Alan Natali’s Brown’s Town, team captain Tony Adamle, later a physician, recalled Ford at practice one day: “[T]he snow was all over the ground, except around him. He had so much booze in him that the snow all melted.” Dub Jones said Brown didn’t press the discipline issue when it came to the league’s best defensive end. “He backed off, and the players recognized that he backed off.” Don Colo said Ford “had no peers on the field but was a lousy person off the field. . . drunk all the time.”

No longer running pass routes, Ford’s bow-legged frame filled out to a formidable 260 pounds. The team revamped its defense to maximize his talents, dropping back two of their six linemen, the origin of the 4-3 alignment. Cleveland allowed the fewest or second-fewest points in each of his eight seasons. Ford was All-Pro five straight years.

|

| From Jet Magazine, Nov. 12, 1953 |

He intercepted two Bobby Layne passes in the 1954 title game triumph over the Detroit Lions, returning one 45 yards in the 56-10 rout. “They beat the hell out of us,” Layne said from the post-game locker room.

Throughout his career, Ford’s dogged quest for quarterbacks led to several on-field skirmishes with offensive linemen (including the Rams’ Bill Lange in 1952, the Lions’Andy Miketa in 1954, the Steelers’ Bob Gaona in 1956, and the Cardinals’ Len Teeuws in 1957), and ejections often ensued.

Beginning of the end of the end

Ford’s last game as a Brown, and as number 80, was in Detroit in 1957. The Lions avenged 1954 to win their last championship, 59-14. Lineman Lou Creekmur, a future Hall of Famer, said he’d never seen the Browns “as dead or flat as they were Sunday. I blocked Lenny Ford and Don Colo most of the afternoon and I don’t ever think I’ve had an easier day in my entire football career.”

The next month, Ford had shoulder surgery, kicking off an awful year. In May, Brown traded the declining 32-year-old to Green Bay for a fourth-round draft pick used on another All-America end from Michigan. Gary Prahst of Berea didn’t make it in the NFL.

Ford was briefly hospitalized with the flu as Packers training camp opened. In October, facing Creekmur again, he got frustrated by the officials’ failure to call holding, lost his temper and was ejected.

It was the Packers’ worst year ever. In November, they lost 56-0 to Baltimore, then against the Bears had a golden chance for an early touchdown. They called a fake field goal, with holder Bart Starr to pass instead.

Who was all alone in the end zone? Len Ford, the former two-way threat who hadn’t seen a pass thrown for him in nine years. Starr lobbed the ball right to him, but it fell to the ground through Ford’s battle-ravaged fingers. They lost 24-10 and didn’t sniff victory the rest of the year.

But Ford didn’t even make it that far, fired before the finale for allegedly breaking training rules. Rather than finishing in Los Angeles, site of his old Rose Bowl glory and AAFC exploits, he got flown home. He later claimed in a lawsuit that broken fingers disabled him for the last game, and that the termination not only cost him his $916.66 game check but damaged his reputation.

That month, the golden age of televised football began with the so-called “greatest game ever played,” the sudden-death championship matchup between the Baltimore Colts and New York Giants. Among the dozen future Hall of Famers suiting up that day were defensive ends Andy Robustelli of New York and Gino Marchetti of Baltimore.

But Ford’s career was now over, and months later, so was his marriage. Geraldine would later be elected the first African American woman judge in Michigan. She served on the bench through 1999, and their daughter Deborah followed suit in 2004 through the present.

Ford remained a Detroiter, but little is known beyond his football life. His autographs are considered rare, and some feature a long, exaggerated crossing stroke midway down the “F,” as if to negate his name. He apparently dabbled in real estate and studied law for a time. He later worked as assistant director of a city recreation center.

Ford was a finalist for the Hall of Fame in 1971, the year Robustelli was inducted. Marchetti was announced as an honoree in early February of 1972.

According to press reports, Ford was admitted to Detroit General Hospital on February 15, 1972, with a heart condition. He never made it out. He suffered cardiac arrest on March 6 and died a week later. He was 46 and rests in the same Maryland cemetery that now also holds another famous athlete with his given name: young basketball star Len Bias.

Respected veteran sportswriter and artist Murray Olderman made an offhand reference to Ford in a 1976 column, that he “died drunk and broke in a rundown hotel.” This seems both uncharitable and, if taken literally, in conflict with reports of Ford’s hospitalization. It does, however, leave a vivid impression.

The summer after Ford’s demise, Turkey Joe Jones tore up his knee against Paul Brown’s team in the Horseshoe, and the fate of the Browns’ wearers of 80 turned 180 degrees.

Ford’s legacy, meanwhile, lives on. He was chosen for posthumous enshrinement in Canton in 1976, his fifth time as a finalist. His presenter was his high school coach, Theodore McIntyre. Deborah, then in her early 20s, represented the late Browns great, concluding her speech poignantly.

“Daddy, you’ve made it.”

Never to Rison again

One more honor remains overdue. Teams today are reluctant to retire numbers because they might run out. But if any exception is appropriate, indeed necessary, it’s this one.

In the names of Lenny Ford and Bill Glass specifically, but also in Lahr’s memory, and to recognize all Browns hurt in the line of duty, and really for the franchise’s own good going forward, the Browns ought to retire number 80.

Promptly, permanently, and officially.

Let it rest in peace.

(Author’s note: a version of this piece originally appeared on the Orange & Brown Report in April 2014. Last revised September 22, 2015)