In the NFL, penalties don’t correlate well with winning or losing. Why not?

In theory, penalties reflect getting outplayed by an opponent or a lack of discipline or concentration. Those factors, plus the consequences of the penalties themselves, ought to track at least somewhat with a team’s overall success rate.

Contrary to that, it’s easy to think that in a highly rule-bound sport, many penalties are just unfortunate by-products of a factor more important to winning: aggressiveness.

Both statements above are consistent with the following research finding:

Teams with more offensive penalties generally lose more games, but there is no correlation between defensive penalties and losses. The penalty that correlates highest with losses is the False Start, and the penalty that teams will have called most consistently from year to year is the False Start

In addition, much like society at large, the league just has too many rules to enforce with any regularity. With so much fast-paced action on every play (and in between), the officials are left with a huge amount of discretion, which makes them prone to all manner of human errors — attentional, attributional, and motivational.

The league office pays eagle-eyed attention to the decisions its officials make. That’s out of necessity, of course, but it does introduce other factors affecting how games are called. These sometimes take the form of “points of emphasis,” or de-emphasis too (e.g. fewer offensive holding calls).

One could speculate that officials, knowing they will be graded on things like the type, frequency, and balance of their penalty calls, may act to fulfill the league’s expectations specifically without having a substantial impact on the game’s outcome.

Alternately, a reasonable theory is that penalties — regardless of their “engineering” — aren’t typically a significant enough aspect of the game to tilt scoreboards systematically. Flags follow such a wide assortment of actions that few generalizations apply.

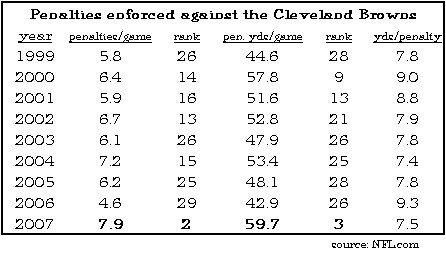

That’s why it’s important to examine each individual call — and its circumstances — for the clues it yields (in isolation or collectively) about a player, a unit, a team, an opponent, and an officiating crew. Given the Browns’ excessive level of penalties this season, I’ll be presenting such an analysis (as I did in 2004, 2005, and 2006) in an upcoming post.